The History of Paint

Living in today's fast paced world of quick fixes and insta-gratification we hardly stop to think of the history of the objects we use, and the many sacrifices that have been made to provide us with utter convenience. Oil Paint, especially, has a dark and grim history. Preparing and grinding pigments for paint was not only a laborious task for any painter (If you've seen the movie Girl with the Pearl Earring you should recall this), but also toxic, gross and often involved animal cruelty.

The old Masters, such as Rembrandt, would surely be jealous of the amount and ease of access we have to paint in modern society.

This also meant that pigments were usually expensive and hard to find. An artist's paint recipe was kept secret, and it was a struggle for artists to find paints that would hold permanency. The search for new, better and brighter colours dominated rational thought in many instances. These are a few of the stories surrounding the history of pigment and paint:

Emerald Green

Napoleon Bonaparte was exiled to the Atlantic Ocean island of St. Helena in 1815 after his defeat at Waterloo. He died six years later in 1821. Autopsy reports indicated that Napoleon had succumbed to a stomach cancer but also indicated high levels of arsenic. There are many theories surrounding the exact cause of Napoleon's illness, but it is generally agreed upon that the high levels of arsenic certainly contributed to and hastened his death. Arsenic poisoning was quite common within this time frame, but Napoleon's alleged silent killer kan be connected to aesthetics.

In 1775 Carl Wilhelm Scheele, a scientist, invented a colour he called Scheele's Green, which was later improved and renamed as Emerald Green. The pigment was originally prepared by making a solution of sodium carbonate at a temperature of around 90 °C, then slowly adding arsenious oxide, while constantly stirring until everything had dissolved. This produced a sodium arsenite solution. Added to a copper sulfate solution, it produced a green precipitate of effectively insoluble copper arsenite. After filtration the product was dried at about 43 °C. To enhance the color, the salt was subsequently heated to 60–70 °C. The intensity of the color depends on the copper : arsenic ratio, which in turn was affected by ratio of the starting materials, as well as the temperature. This deathly colour was used within wallpaper, newspapers, clothing and to colour candles and candy.

This was also reportedly Napoleons favourite colour and was thus used within his rooms and also in his bathroom at St. Helena, where he would spend a lot of time in his copper tub. Later studies revealed that when the wallpaper became damp and moldy, the pigment may be metabolised, causing the release of poisonous arsine gas. More importantly, the island of St. Helena is known for its damp conditions, and even today, the Longwood House needs to be re-wallpapered every few years because of the humidity on the island—making it (and the bathroom) a perfect place for the chemical reaction that would release arsenic into the air.

Mummy Brown

By the 16th century, despite legal restrictions, exporting mummies from Egypt to Europe to be ground up and used as “medicine” was big business, "mummy" or “mumia”, was typically the ground-up body, or body parts, applied topically to be rubbed on, or mixed into drinks to swallow. Its medical benefits were proclaimed in standard pharmacopoeia and extensively promoted by physicians, apothecaries and barber-surgeons. By the 16th and 17th centuries it had become one of the most common drugs found in the apothecaries’ shops of Europe.

Given that Europeans happily ate, drank and rubbed mummy on themselves, you should not now be surprised to hear that they also painted with it. The product they used was called “Mummy Brown” – a rich brown pigment made from the flesh of mummies, mixed with white pitch and myrrh. It was also known as Caput Mortuum or Egyptian Brown. As a brown pigment with good transparency, it could be used as an oil paint, and possibly as a watercolour pigment, for glazing, shadows. flesh tones(!) and for shading.

The pigment achieved its greatest popularity in the mid-eighteenth to nineteenth centuries and, in 1849, was described as being “quite in vogue”. It was, for example, one of the pigments on Delacroix’ palette in 1854, when painting the Salone de la Paix at the Hotel de Ville. The British portraitist Sir William Beechey was recorded as having stocks of it. The French artist Martin Drölling also reputedly used Mummy Brown made with the remains of French kings disinterred from the royal abbey of St-Denis in Paris.

Vermilion

Vermilion (sometimes spelled vermillion) is a brilliant red or scarlet pigment originally made from the powdered mineral cinnabar, the ore which contains mercury and like most mercury compounds it is toxic. It was widely used in the art and decoration of Ancient Rome, in the illuminated manuscripts of the Middle Ages, in the paintings of the Renaissance, as sindoor in India, and in the art and lacquerware of China.

Cinnabar pigment was a side-product of the mining of mercury, and mining cinnabar was difficult, expensive and dangerous, because of the toxicity of mercury. The Chinese were probably the first to make a synthetic vermilion as early as the 4th century BC. Mercury and sulfur were mixed together, forming a black compound of sulphide of mercury, called Aethiopes mineralis. This was then heated in a flask. The compound vaporized, and recondensed in the top of the flask. The flask was broken, the vermilion was taken out, and it was ground. When first created the pigment was almost black, but as it was ground the red color appeared. The longer the color was ground, the finer the color became. The Italian Renaissance artist Cennino Cennini wrote: "if you were to grind it every day even for twenty years it would keep getting better and more perfect."

During the 17th century a new method of making the pigment was introduced, known as the 'Dutch' method. Mercury and melted sulfur were mashed to make black mercury sulfide, then heated in retort, producing vapors condensing as a bright, red mercury sulfide. To remove the sulfur these crystals were treated with a strong alkali, washed and then ground under water to yield the commercial powder form of pigment.The pigment is still made today by essentially the same process.

Vermilion was the primary red pigment used by European painters from the Renaissance until the 20th century. However, because of its cost and toxicity, it was almost entirely replaced by a new synthetic pigment, cadmium red, in the 20th century.

Genuine vermilion pigment today comes mostly from China; it is a synthetic mercuric sulfide, labeled on paint tubes as PR-106 (Red Pigment 106). The synthetic pigment is of higher quality than vermilion made from ground cinnabar, which has many impurities. The pigment is very toxic, and should be used with great care

Flake White

Flake White was produced by stacking lead strips in a confined space with vinegar and animal dung. Evidence can be found to suggest that Flake White has been used since 400 BC. As one of the earliest pigments, Flake White is a basic lead carbonate with zinc oxide and up to the 19th century was one of the only available white pigments for artists. Flake White is seen by many as one of the finest pigments as it's reaction to oil gives a flexible and permanent paint film. Even though most lead paints are banned today, one can still purchase Flake White as well as Cremnitz White. These paints are however toxic, and caution should always be taken.

Tyrian Purple

The colour used in Roman togas for dignitaries. 1.4 grams of the dye could be attributed to the killing of 12000 molluscs, and this would only die the trim of a garment. The dye substance is a mucous secretion from the hypobranchial gland of one of several species of medium-sized predatory sea snails that are found in the eastern Mediterranean Sea.In nature the snails use the secretion as part of their predatory behaviour in order to sedate prey and as an antimicrobial lining on egg masses. The snail also secretes this substance when it is attacked by predators, or physically antagonized by humans (e.g., poked). Therefore, the dye can be collected either by "milking" the snails, which is more labour-intensive but is a renewable resource, or by collecting and destructively crushing the snails.

The Phoenicians also made an indigo dye, sometimes referred to as royal blue or hyacinth purple, which was made from a closely related species of marine snail.

Although the dye trade was a worthwhile one, "stinking like a phoenician" became a popular insult in this era, as the process of milking or crushing sea slugs was not a process that appealed to the olfactory sense.

Ultramarine

Ultramarine is a deep blue color and a pigment which was originally made by grinding lapis lazuli into a powder. The name comes from the Latin ultramarinus, literally "beyond the sea", because the pigment was imported into Europe from mines in Afghanistan by Italian traders during the 14th and 15th centuries. Ultramarine was the finest and most expensive blue used by Renaissance painters. It was often used for the robes of the Virgin Mary, and symbolized holiness and humility.

Ultramarine cost up to 300 francs per kilogram, due to its expensive ingredient of cobalt. However in 1826, in a competition held between French and Germany a synthetic Ultramarine, or French Ultramarine, as it is more commonly known was invented.

Cochineal

Cochineal is probably from French cochenille, Spanish cochinilla, Latin coccinus, meaning "scarlet-colored", and Latin coccum, meaning "berry (actually an insect) yielding scarlet dye/pigment.

Production methods for cochineal dye have been found within the aztec codices and it is widely accepted that the Aztecs and Mayans used cochineal as a dye. During the colonial period, the production of cochineal grew rapidly. Produced almost exclusively in Oaxaca by indigenous producers, cochineal became Mexico's second-most valued export after silver. Soon after the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, it began to be exported to Spain, and by the 17th century was a commodity traded as far away as India. The dyestuff was consumed throughout Europe and was so highly prized, its price was regularly quoted on the London and Amsterdam Commodity Exchanges.

These are a few pigments I received from South America. Take note of the Rosado and Rojo pigments both made from Cochineal.

The demand for cochineal fell sharply with the appearance on the market of Alizarin Crimson and many other artificial pigments discovered in Europe in the middle of the 19th century, causing a significant financial shock in Spain as a major industry almost ceased to exist. The delicate manual labour required for the breeding of the insect could not compete with the modern methods of the new industry, and even less so with the lowering of production costs. The "tuna blood" dye (from the Mexican name for the Opuntia fruit) stopped being used and trade in cochineal almost totally disappeared in the course of the 20th century. The breeding of the cochineal insect has been done mainly for the purposes of maintaining the tradition rather than to satisfy any sort of demand.

It has however become commercially valuable again. One reason for its popularity is that many commercial synthetic red pigments were found to be carcinogenic

Cochineal is used as a fabric and cosmetics dye and as a natural food colouring. It is also used in histology as a preparatory stain for the examination of tissues and carbohydrates. In artists' paints, it has been replaced by synthetic reds and is largely unavailable for purchase due to poor lightfastness. Natural carmine dye used in food and cosmetics can render the product unacceptable to vegetarian or vegan consumers.

Cochineal is one of the few water-soluble colourants to resist degradation with time. It is one of the most light- and heat-stable and oxidation-resistant of all the natural organic colourants and is even more stable than many synthetic food colours. The water-soluble form is used in alcoholic drinks with calcium carmine; the insoluble form is used in a wide variety of products. Together with ammonium carmine, they can be found in meat, sausages, processed poultry products, surimi, marinades, alcoholic drinks, bakery products and toppings, cookies, desserts, icings, pie fillings, jams, preserves, gelatin desserts, juice beverages, varieties of cheddar cheese and other dairy products, sauces, and sweets.

Carmine is considered safe enough for cosmetic use in the eye area. A significant proportion of the insoluble carmine pigment produced is used in the cosmetics industry for hair- and skin-care products, lipsticks, face powders, rouges, and blushes. A bright red dye and the stain carmine used in microbiology is often made from the carmine extract, too. The pharmaceutical industry uses cochineal to colour pills and ointments.

With the boost of automobiles in the last century, scientists had to figure out how to spray cars with colours that would last and not fade in the rain or sunshine. Artists can thus thank the car industry for the wide range of permanent paints that are now available.

Interested in buying real Ultramarine or Cinnabar pigment? Check out these websites: http://www.masterpigments.com or http://www.naturalpigments.com/

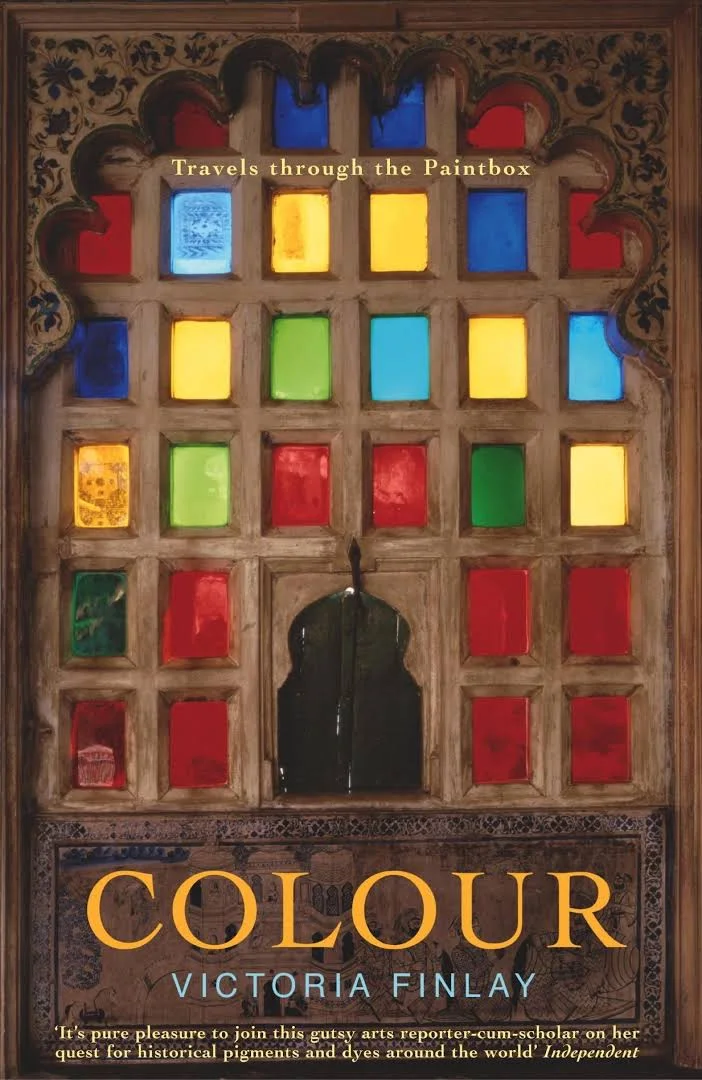

If you found this very interesting and would like to know more, I would definitely recommend reading Colours by Victoria Finlay. You can get this here if you're in South Africa.

So the next time you hold a tube of paint in your hand and wonder if it's too expensive, think about the history and all the experiments and adventures it took to get to you.